Environmental Brains over Brawn for the 21st Century

courtesy of New York Times: September 22, 2005

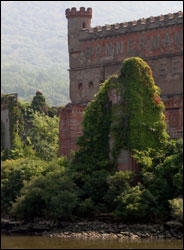

Castle in Ruin, on a River That Nearly Was

By ANTHONY DePALMA

BEACON, N.Y. - As John Cronin sails toward the ruins of Bannerman's Island in the broad belly of the Hudson River, he sees a symbol of the challenges facing the waterway where he has spent much of his adult life.

He expertly pilots his 29-foot fishing boat, Trust, through the unmarked shallows to dock below the wrecked castle about 1,000 yards off the Beacon shore. Built a century ago by an eccentric arms dealer, it is a haunting relic of the past, and a metaphor for the Hudson's future.

"It's not just about fighting pollution anymore, it's about rebuilding the estuary," he said.

Mr. Cronin is 55, though he looks 20 years younger, with a full head of ginger hair and just an ice-cream drip of grey in his beard.

Few know the Hudson as he does. In the 1980's he spent two and a half years as a commercial fisherman on the river - which is actually an arm of the ocean, or salt-water estuary, for much of its length. He was better at talking than at netting sturgeon or American shad, so the Hudson River Fishermen's Association, an environmental watchdog group of sports and commercial fishermen, enlisted him as the Hudson's first river keeper. He held that position for 17 years, patrolling for polluters and fighting for the river.

When he turned 50 in 2000, he decided it was time for a change, and he left Riverkeeper, a private, nonprofit environmental organization founded in 1983 when the Hudson was a contaminated industrial pipeline of a river. With money from foundations and private contributors, Riverkeeper sued polluters and worked to convince the people of the Hudson Valley that they needed to roll up their sleeves and protect the river themselves.

Though he left Riverkeeper, Mr. Cronin did not leave the river. He become director of Pace University's Academy for the Environment. He is also managing director of the Rivers and Estuaries Center in Beacon, and is one of the few people with special permission from the state's parks department to visit Bannerman's Island.

Mr. Cronin said that he welcomed recent news that the Hudson was clean enough for several beaches to be opened for swimming, and that the major lawsuits brought by Riverkeeper's lawyer, Robert F. Kennedy Jr., and others over the years have turned the river around significantly.

But a bit of the fisherman is still with him: a pragmatism born of cold mornings on the river and big plans smashed by a bad catch. He says there might be just a little too much backslapping going on about how clean the river is, and not enough recognition that the old ways of doing things just don't work anymore.

In saying that the fight for the Hudson must take a new tack, Mr. Cronin is putting forward what might be considered a Hudson River version of "The Death of Environmentalism," the 2004 essay that roiled environmentalists with charges that outmoded concepts, confrontational methods and a lack of inspiring vision had sapped the movement's power.

Despite many early successes, fish species have dwindled or disappeared, PCB's still poison the river bottom, recreational access to the water is extremely limited, and pollutants continue to pour into what television commentator Bill Moyers called "America's first river."

Yet comparatively little money is spent on research, Mr. Cronin said, and public perception is skewed. Polls show that many people are reluctant to spend much time or money helping the river because they believe that it is already healthy.

In a recent survey conducted by Pace University, in cooperation with the Academy for the Environment, 55 percent of those responding rated the environment as excellent or very good. And 84 percent thought that polluting the Hudson was illegal.

But the major federal legislation on water pollution, the Clean Water Act of 1972, does not ban the discharge of all pollutants into the nation's waterways. The law only regulates what can be dumped into rivers, like the Hudson, where some industrial pollutants and wastewater from sewage treatment plants are still allowed with a state permit.

The environmental movement on the Hudson needs a new vision, Mr. Cronin said, one less focused on science and more in touch with the whole river system, including the communities along its banks. And just as a group of local people and businesses from the Beacon area are trying to stabilize what remains of the buildings on Bannerman's Island and open them to tourists, he says that the Hudson should be revitalized so it can again be a natural resource and economic engine for the region.

"I don't think that rebuilding Bannerman's Island or restoring all the fish species to the Hudson is any more difficult than any of the other things we've accomplished so far," Mr. Cronin said from the decayed brick balcony of what remains of the Bannerman complex, about 50 miles north of New York City.

A fire in the 1960's gutted the island's main residence and turned the improbable five-story brick arsenal where Francis Bannerman stored his huge stock of Army-surplus weapons into ghostly ramparts that could haunt a youngster's dreams.

When he was a boy growing up in Yonkers, Mr. Cronin said, the only thing he knew about the Hudson was that he should stay away from it because it was dirty. "The word polluted wasn't used back then," he said. He dreamed of becoming a baseball player before he fell in love with the river. Now his dream is to see the day when all discharges of pollutants are outlawed, a provision of the Clean Water Act that was abandoned in federal legislation. "Since zero discharge was a centerpiece of the Clean Water Act, it should be the centerpiece of the Hudson's future," he said. But even though he has been involved in more than 100 environmental lawsuits, he said, he does not believe that this goal can be achieved by going back to court. Rather, he said, a new era in the movement is beginning.

"The 20th century was the era of environmental brawn," he said. "The 21st century must be the era of environmental brains."

Mr. Cronin is not alone in taking this view. The Garrison Institute, a nonprofit organization based in a renovated monastery in the Hudson Highlands, has begun a series of meetings to bring together environmentalists and faith-based religious groups to find a common language in the stewardship of the river.

"We have to start by redefining what the river is," said Jonathan F. P. Rose, a founder of the institute. Earlier environmental battles were based on the science of stopping pollution, he said, but now the river must be seen as a part of a whole system that includes the communities alongside it and the effects of storm water runoff, sewage discharges and suburban sprawl.

Mr. Rose said the bitter confrontations that pitted environmentalists against industry will no longer work. Mr. Cronin agrees, and that is quite a conversion for a man who spent years painting industries like G.E. as willful polluters.

He sees things differently now. "We can't afford to have industry be permanent adversaries," he said. Rather, it is necessary to build partnerships that can bring together scientists, engineers, businesses, policy makers and environmentalists.

Mr. Cronin has started organizing the Environmental Consortium of Hudson Valley Colleges and Universities, 37 institutions that will make studying the Hudson River a priority.

And as he navigates Trust through the muddy shallows and back to the run-down landing in Beacon, Mr. Cronin is careful to keep an eye on the shifting current. Similarly, he says, it is important to keep on top of shifts in perceptions.

"We environmentalists fighting for the river and bragging about our successes are probably not as in touch with public perceptions as we think we are," he said. "Anybody of my daughter's generation, and she is 30, has every right to say to me when I'm talking about the past, 'That's an interesting story but I want to know what's going to happen in the next year, or the next five years.' "

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home